Asked for the names of people still hand-making silver Boehm-system flutes in Britain, most flautists would struggle beyond two or three. It might seem the great tradition that reached its flowering in the work of Albert Cooper has wilted. Many will be surprised therefore to learn of a craftsman working at home in much the same circumstances who, over the past twenty years, has produced a series of peerless flutes. That they are little-known owes much to their maker's discretion and owners' satisfaction - so far none has been resold on the open market.

British Flutemakers: William Simmons

William Simmons: A Flutemaker in the Great Tradition

In fact the name of this flutemaker isn't unfamiliar in flute circles. But William Simmons is associated mostly with headjoints and enjoys a reputation as a master repairer, the kind other repairers resort to when stumped. His passion however for many years has been designing and making silver flutes, thirty-seven so far owned and played by discerning flautists in Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia.

For Albert Cooper and others of his generation, the way to become a flutemaker was still through an apprenticeship, in his case at Rudall Carte. But the story of how someone arrived at flutemaking once that traditional path had closed is both fascinating in its own right and instructive for the future.

William (Willy) Simmons is a Lancastrian, born and brought up at Kearsley and Little Hulton near Bolton. The sounds of engineering and music filled his home, his father and grandmother playing the piano and his father keeping a lathe for making and restoring clocks. Willy's flutemaking, he says, started the day he took his grandmother's clock apart and tried to put it back together. Inspired by his father, whom he remembers as a wonderful engineer, he then set about making a perpetual motion machine in Meccano. He played the recorder and sang in the church choir. Music tuition came from his grandmother and the choirmaster, who also ran a dance band featuring two saxophones. Willy duly took up the tenor sax and later the flute. He went on to serve his playing apprenticeship playing blues in clubs such as The Jungfrau in Manchester and The Cavern in Liverpool. When his Conn saxophone came back from the repairer in poor order, he did the job himself and discovered a skill and sense of satisfaction that has never left him.

After studying, playing and teaching music in London, Arthur Haswell moved to Northumberland where he repairs and restores flutes.

His reputation as a player reached Chris Blackwell, who offered him a retainer and any amount of work with artists on Island Records. So in 1966, at the start of the greatest modern musical boom, Willy moved to London, playing sessions by day and gigs in the evening, followed by private parties where musicians gathered to jam into the early hours. With no time to take his instruments to a repairer, he learned to do the job himself. He ran through a variety of flutes, trying and assessing everything from a Boosey & Hawkes Regent, to a French flute, a Bonneville, and on to a series of German flutes, including an aluminium Uebel which was very stout mechanically- an important factor when playing an average of nine bookings every week.

His repairing skills led other players to entrust their flutes to him. Some asked for modifications and so he began customising keywork. In session work he found the alto flute particularly popular and saw the opportunities for a bass flute, in those days a rare instrument. Without having one to copy, he devised a scale by calculation, made the parts and several prototype bodies to establish the tuning, and had almost finished the flute when it was stolen.

During those years Willy played on many records, toured with visiting American stars, and shared the famous stages of The Marquee and the ioo Club with musicians such as Graham Bond, Spencer Davis, Jimi Hendrix, Albert Lee, Zoot Money, and Jimmy Page. At last, tired of the unrelenting schedule, he quit and returned to Kearsley. Having come to prefer the flute to the sax, its pure conception and construction appealing to his perfectionism, he decided to study it properly and took lessons with Joan Simpkin and Geoffrey Gilbert, while playing in a folk duet and later in opera and pit bands.

His reputation as a technician had followed him home and over the next decade he established himself as a repairer nationwide. Seeing a great variety of flutes, he came to appreciate the well-designed and skilfully-made. In particular he was lucky enough to work regularly on Cooper and Almeida flutes, an experience that opened his eyes to how beautiful and finely constructed a flute could be.

In the 1980s he went to America, where he met Edward Almeida and visited the Brannen and Powell factories. A trip to Belfast on his return brought him into contact with a flute band that needed a new G treble - a harmony flute half way to becoming a piccolo. Willy set about making them one. In order to establish a scale he measured a dozen G trebles, noting what he thought was wrong with each of them and mathematically correcting the faults. After making a couple of prototypes he finished his first Simmons flute.

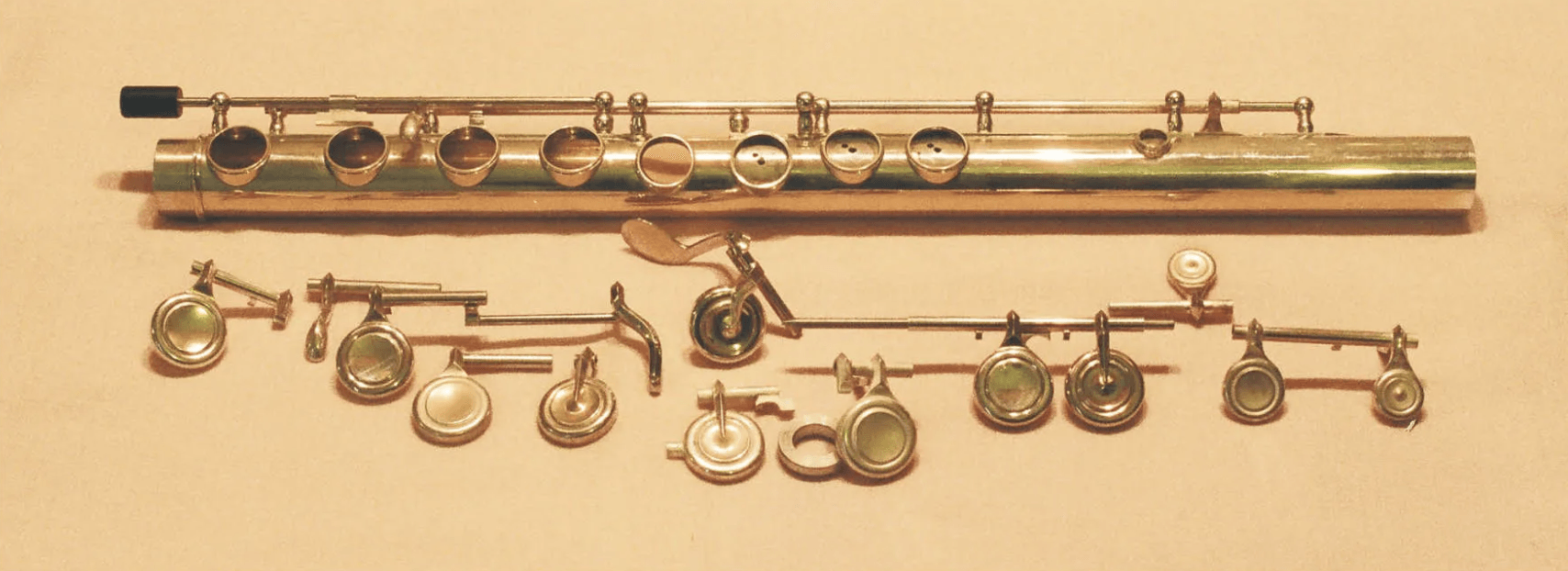

He made two more G trebles for bands in Ireland and Scotland before turning his attention to the huge task of designing a standard concert flute. He consulted a number of makers of whom Harry Seeley, who'd worked at Rudall Carte and was then at Flutemakers Guild, was particularly helpful. As before, to devise a scale Willy measured as many professional flutes as he could find. The scales used by Japanese makers he found too disparate to be considered. He studied a number of Cooper flutes and discovered a pattern that showed how Albert Cooper had sought to bring his instruments up to modern pitch. Across a selection of Boston-made flutes, all supposedly built to a fixed scale, he noted an inconsistency in manufacture that left them all different. But by employing his previous method of deciding what was wrong and making calculations to put that right he established, through a series of three prototypes, a satisfactory scale and design, and went on to make a flute in silver with closed holes.

While his original scale was largely a success, in subsequent flutes he continued to make minor alterations to the position and size of tone-holes. In devising a scale, he says, there are always compromises, and the art lies in knowing which compromises to allow. Players, he points out, often do not appreciate this need for informed compromise. He himself has striven to find the balance.

So far Willy Simmons has made a total of twenty-five standard concert flutes and twelve G-trebles. When preparing to make a flute, Willy asks, 'How can I improve on the last one? How can I make this next one the best?' The result is that each flute is different, a unique whole, the fact their maker is never satisfied in no way invalidating any of them. As he is keen to point out, he doesn't regard any as inferior. Some of his flutes have open holes, some closed. A few are open G sharp. Two feature automatic F sharp mechanisms which close the A key. Apart from two built to special order he has fitted an E-mechanism to all (except, of course, the ones with an open G sharp).

Just as he could have produced many more flutes had he established a pattern and kept to it, turning out over and over again the same model, so his work would be easier if he bought in parts, as some flutemakers prefer, for instance fitting Brannen keywork to a hand-made body. For Willy that would preclude continuous development and rule out the fine tolerances that elevate his flutes. This is nowhere better illustrated than in his approach to the problem of allowing for the different tuning characteristics of an open-hole compared to a closed-hole flute. To compensate for the slightly higher pitch given by open hole keys, makers generally move each tone-hole and key cup one millimetre down the body. But, as Willy points out, the actual amount needed increases with the distance from the head joint, like the spacing of frets on a guitar. Making everything himself, he is able to design this precise proportional increase into his open-hole flutes, giving them a truer scale.